Electoral reforms may threaten democracy in Greece

Changing voting systems is harder than simply passing a law - Published in Young Voices Europe

This article was published on the Young Voices Europe Blog, I encourage you to read it here.

Believe it or not, the “birthplace of democracy” isn’t perfectly democratic. For Greeks, the conflict between strong leadership and representative democracy isn’t a new one. But with the Government announcing elections to take place as early as April, that ancient debate will soon face a modern test. This coming election will use proportional representation (PR). The subsequent one will almost certainly not. Opposition parties will have to seize their opportunity to protect future elections.

At the heart of these electoral fluctuations lies Clause 1, Article 54 of the Greek constitution. It sets out that any changes to the Greek electoral system can only take place in two elections’ time, unless voted through with a supermajority. Because of this, Syriza’s (the former government) 2016 electoral reforms are only coming into play now, seven years (and one election) later. In 2020, the current New Democracy (ND) government undid Syriza’s shift towards proportional representation, moving the system back to reinforced proportionality (RP) – where the winning party gets “bonus” seats, on top of their proportionally allocated ones.

Those changes are only set to come through in the 2027 election. However, New Democracy has an odious plan to circumvent the spirit of the constitution. By simply running one election, refusing to form any government (majority or coalition) and thus forcing an immediate second election, under their new system, they are attempting to legislate themselves a majority.

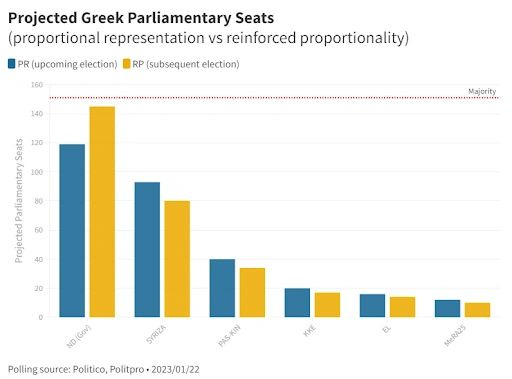

The numbers paint a clear picture:

The government’s party is projected to net 25 extra seats of the 300 total from a rerun, with the same share of the vote. When you take into account a subsequent, refocused campaign on a “strong and stable government” and further polarisation, prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis believes he can in this way hold onto his parliamentary majority.

Now, the government isn't breaking any rules, and you can hardly expect politicians not to take advantage of circumstances when they see the opportunity. In fact, you could even go as far as to commend the relative lack of politicking by the current government (up until this point). Throughout the pandemic, they resisted the temptation to call an early election under more favourable polling, and have effectively fulfilled their four-year term. And the new electoral rules are an improvement on the system that preceded Syriza’s changes, under which they’d already be on track for a majority.

Nevertheless, the current state of affairs warrants intervention from opposition parties. If and when New Democracy refuses to try to form a government after the first election, the buck is passed to the next largest party. For Alexis Tsipras, leader of Syriza, this would present an opportunity for another run at power, after losing to Mitsotakis in 2019. He has already stated his election goal of securing a progressive coalition government in the first round of voting, hoping to avoid a second election. Although his party would also benefit from the new rules if they led in the polls, he is ideologically inclined to help push Greece back towards proportional representation.

Smaller opposition parties have an even greater incentive to work with Syriza to make this happen. Reinforced proportionality shrinks their relative share of the vote and greatly reduces the chances that a coalition is necessary to form a government. If not for the Greek people, smaller parties should be doing this for themselves and their own prospects of power.

What’s more, with the government still embroiled in a wire-tapping scandal dubbed the “Greek Watergate”, many parties would benefit from a public display of opposition, especially if another election is around the corner.

Strong incentives exist, both moral and political, for the formation of a unity government. Even if you buy into the government's rhetoric (that a strong and stable government is what helped pull Greece out of its financial woes and into the strongest economic recovery in the OECD, and is what is needed to continue that growth) the imperative is still strong. Chances are that even if a unity government forms, it will collapse sooner rather than later, bringing forth a fresh election with reinforced proportionality followed by proportional representation in 2027. It’s a win-win situation.

Everything playing out to plan does seem more Netflix than not. But in the past, Greek politicians haven’t been afraid to dabble in drama and chaos, especially with power and self-preservation on the line. If they can shift their focus beyond the next four years – to the four that follow – they can protect the future of a fairer, more representative and ultimately more democratic Greece.